A Complete Guide to Memory Management in C++

Introduction: The Power and Responsibility of C++

As C++ creator Bjarne Stroustrup once said, “C makes it easy to shoot yourself in the foot; C++ makes it harder, but when you do, you blow your whole leg off.” This quote perfectly captures the essence of memory management in C++.

Unlike languages with automatic garbage collection like Java or C#, which have an internal process to release memory, C++ grants the programmer direct control over memory. This control is a primary source of its power and performance, allowing for the creation of extremely fast and efficient code.

However, this control comes with the responsibility of managing resources manually. A failure to release an unused resource is called a memory leak. A leaked resource becomes unavailable for reuse by the program itself, gradually consuming memory until the process exits. Memory leaks are a common cause of bugs and instability.

This guide will equip you with the principles and modern techniques to manage memory safely and effectively in C++. The goal is to transform what can be a daunting task into a manageable and systematic one, enabling you to write C++ code that is not only powerful but also robust and safe.

1. The Two Worlds of Memory: The Stack and The Heap

A C++ program primarily uses two distinct areas of memory for its data: the Stack and the Heap (also known as the free store).

- The Stack The stack is a highly organized and fast region of memory where data is allocated and deallocated automatically. It operates on a “Last-In, First-Out” (LIFO) principle. The stack is where local variables and function call information are stored. When a function is called, its variables are “pushed” onto the stack; when the function exits, they are automatically “popped” off. Its primary limitation is its fixed and relatively small size.

- The Heap The heap is a large, less organized pool of memory available for data that needs to have a long lifetime or is too large to fit on the stack. Unlike the stack, memory on the heap must be allocated and deallocated manually by the programmer using the

newanddeleteoperators. While flexible, this manual control is where most memory management errors occur.

The following table synthesizes the key differences between these two memory regions.

| Feature | The Stack | The Heap (Free Store) |

|---|---|---|

| Allocation/Deallocation | Automatic (managed by the compiler) | Manual (managed by the programmer via new/delete) |

| Speed | Fast allocation and deallocation | Slower due to more complex management |

| Size | Fixed and limited in size (~2MB) | Large and flexible |

| Management | Managed by the compiler/runtime (via function calls) | Handled by the programmer and memory manager |

| Risk | Low risk of errors | Prone to errors like fragmentation and leaks |

It is important to note that the actual physical location of these two areas of memory is ultimately the same, the RAM.

Understanding the difference between the stack and the heap is fundamental, as the most common and dangerous errors arise from mismanaging the heap.

2. The Perils of Manual Memory Management

C-style or “naive” C++ approaches to memory management are a frequent source of bugs. A common but unreliable approach is the “Sandwich Pattern,” where a call to new is followed by some working code and then a corresponding call to delete. This pattern is insidious because it offers no guarantee that the delete statement will ever be reached — an exception or a premature loop exit can easily cause it to be skipped, leading to a memory leak.

2.1. Memory Leaks: The Silent Resource Drain

A memory leak occurs when heap-allocated memory is no longer needed by the program but is not released back to the operating system with delete. This memory becomes unusable for the remainder of the program’s execution, slowly draining available resources.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

void cause_a_leak() {

// Memory is allocated for an integer on the heap.

int* leaky_ptr = new int(42);

// The function returns, but `delete leaky_ptr;` was never called.

// The pointer `leaky_ptr` is gone, but the memory it pointed to is now lost.

} // Memory leak occurs here.

2.2. Dangling Pointers: Touching Freed Memory

A dangling pointer is a pointer that continues to point to a memory location that has already been deallocated (freed via delete). Attempting to access or use a dangling pointer leads to undefined behavior, which can manifest as corrupted data, unexpected crashes, or security vulnerabilities.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

void create_dangling_pointer() {

int* ptr = new int(10);

int* dangling_ptr = ptr;

// The memory is freed.

delete ptr;

// `dangling_ptr` now points to deallocated memory.

// Using it here is dangerous and results in undefined behavior.

// *dangling_ptr = 100; // CRASH! Or worse...

}

2.3. Double Free: Deleting Twice

A double free error occurs when the program attempts to delete the same memory location more than once. This action also leads to undefined behavior and can corrupt the internal data structures that the heap manager uses to track memory, often leading to a crash.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

void cause_double_free() {

int* ptr = new int(20);

delete ptr;

// Attempting to delete the same memory again is a serious error.

// delete ptr; // Undefined behavior!

}

2.4. Buffer Overruns & Underruns: Out of Bounds

C++ does not have built-in range checking for raw arrays. This means it is possible to write or read past the allocated boundaries of an array, an error known as an “invalid write” or “invalid read.” This is a major source of security vulnerabilities, as it can be exploited to overwrite critical program data or execute arbitrary code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

void buffer_overrun() {

// Allocate a heap array for 10 integers (indices 0 through 9).

int* numbers = new int[10];

// This loop writes one element past the end of the array.

for (int i = 0; i <= 10; ++i) { // Off-by-one error: should be i < 10

// On the last iteration (i=10), we write out of bounds.

numbers[i] = i; // Invalid write!

}

delete[] numbers;

}

2.5. Heap Fragmentation: The Checkerboard of Memory

When a program performs many frequent allocations and deallocations of small objects on the heap, the memory can become fragmented. Imagine a solid block of memory that, over time, turns into a checkerboard of used and free chunks.

The primary consequence is that even if the total amount of free memory is sufficient, the program may be unable to find a single contiguous block large enough to satisfy a large allocation request. This can slow down an application or, in extreme cases, cause it to fail.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

// Heap Fragmentation Simulation

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

#include <new>

int main() {

// We will simulate frequent allocations of small amounts of memory

const int NUM_SMALL_CHUNKS = 10000;

const size_t SMALL_SIZE = 64; // Small objects like station codes

std::vector<char*> pointers;

std::cout << "Step 1: Filling the heap with small chunks...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_SMALL_CHUNKS; ++i) {

pointers.push_back(new char[SMALL_SIZE]);

}

// Step 2: Create the "Checkerboard"

// We deallocate every second chunk. This leaves holes of free memory

// separated by small "islands" of still-allocated memory.

std::cout << "Step 2: Creating a checkerboard pattern by deallocating every other block...\n";

for (int i = 0; i < NUM_SMALL_CHUNKS; i += 2) {

delete[] pointers[i];

pointers[i] = nullptr;

}

// Step 3: Attempt a large contiguous allocation

// Total free memory is (NUM_SMALL_CHUNKS / 2) * SMALL_SIZE.

// However, the largest *contiguous* block is only SMALL_SIZE.

size_t large_request = SMALL_SIZE * 5;

std::cout << "Step 3: Attempting to allocate a large block: " << large_request << " bytes...\n";

try {

char* large_block = new char[large_request];

std::cout << "Success: Contiguous block found!\n";

delete[] large_block;

} catch (const std::bad_alloc& e) {

// The heap manager cannot find a single block large enough

std::cerr << "Failure: " << e.what() << " - The heap is too fragmented! [2]\n";

}

// Cleanup remaining pointers

for (auto p : pointers) if (p) delete[] p;

return 0;

}

These classic pitfalls demonstrate that manual memory management is fragile because it relies on the programmer to perform cleanup. Modern C++ provides a robust philosophy that solves these problems by making cleanup and .

3. The Guiding Principle: RAII (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization)

RAII is the central pillar of modern C++ resource management. The principle is simple yet powerful: resource ownership should be tied to an object’s lifetime. This means that an object should acquire a resource in its constructor and release it in its destructor.

The RAII lifecycle works in three deterministic steps:

- A resource (such as heap memory, a file handle, or a network socket) is acquired in an object’s constructor.

- The owning object is declared on the stack.

- When the object goes out of scope (for example, at the end of a function), its destructor is automatically and guaranteed to be called. The destructor then releases the resource.

This pattern makes resource release deterministic and automatic, ensuring that resources are properly cleaned up even if errors occur or exceptions are thrown.

Let’s look at a practical example.

Before RAII (Manual Management) Here, the widget class manually allocates and deallocates memory, requiring an explicit destructor.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

class widget {

private:

int* data;

public:

widget(const int size) {

data = new int[size]; // 1. Acquire resource in constructor

}

~widget() {

delete[] data; // 3. Release resource in destructor

}

void do_something() {}

};

void functionUsingWidget() {

widget w(1000000); // 2. Object is created on the stack

w.do_something();

} // w goes out of scope, its destructor is automatically called.

Modern C++ with RAII (Using a Smart Pointer) By using a smart pointer (std::unique_ptr), we delegate memory ownership to a dedicated RAII object. This eliminates the need for an explicit destructor in our class, making the code simpler and safer.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

#include <memory>

class widget {

private:

std::unique_ptr<int[]> data; // The smart pointer now owns the memory

public:

widget(const int size) {

data = std::make_unique<int[]>(size); // 1. Resource is acquired

}

// 3. No explicit destructor needed! The unique_ptr handles it.

void do_something() {}

};

void functionUsingWidget() {

widget w(1000000); // 2. Object created on the stack

w.do_something();

} // w goes out of scope, its member `data` is automatically destroyed, releasing the memory.

RAII is the philosophy, and smart pointers are the primary tool you will use to implement it for dynamically allocated memory.

4. The Modern Toolkit: Smart Pointers

Smart pointers are class templates provided by the C++ Standard Library. They act as wrappers around a raw pointer, automatically managing its lifetime and ensuring that the memory it points to is correctly deallocated. They are the C++ way of enforcing RAII for heap memory.

4.1. std::unique_ptr: The Default Choice for Exclusive Ownership

A std::unique_ptr maintains exclusive ownership of a heap-allocated object. This means:

- It cannot be copied. You can only move ownership from one

unique_ptrto another. - This rule is enforced at compile time, guaranteeing that only one

unique_ptrcan own the resource at any given time. - It is a “zero-cost abstraction”, meaning it has no performance or memory overhead compared to a raw pointer.

For these reasons, std::unique_ptr should be your default choice for managing dynamic memory.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

#include <iostream>

#include <memory>

void use_unique_pointer() {

// Create a unique_ptr using std::make_unique (preferred way since C++14).

auto my_ptr = std::make_unique<int>(42);

std::cout << "Value: " << *my_ptr << '\n';

// No need to call delete. The memory is automatically freed when my_ptr goes out of scope.

} // my_ptr is destroyed here.

4.2. std::shared_ptr: For Shared Ownership Scenarios

A std::shared_ptr is used when a resource needs to be owned by multiple pointers simultaneously.

- It uses a technique called reference counting. It keeps a count of how many

shared_ptrinstances are pointing to the resource. - The resource is only deleted when the last

shared_ptrpointing to it is destroyed, causing the reference count to drop to zero. - Trade-off: This flexibility comes at a cost.

shared_ptrincurs a small performance overhead for storing and atomically updating the reference count.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

#include <iostream>

#include <memory>

void use_shared_pointer() {

std::shared_ptr<int> ptr1;

{

// Create a shared_ptr. Reference count is 1.

auto ptr2 = std::make_shared<int>(100);

// Copy the shared_ptr. Both now point to the same memory.

// The reference count becomes 2.

ptr1 = ptr2;

std::cout << "Value: " << *ptr1 << '\n';

} // ptr2 goes out of scope. Reference count drops to 1. The memory is NOT deleted.

std::cout << "ptr1 is still valid." << '\n';

} // ptr1 goes out of scope. Reference count drops to 0. The memory is now deleted.

4.3. Choosing the Right Smart Pointer

This table provides a clear guide for when to use each type of pointer.

| Pointer Type | Ownership Semantics | Performance Overhead | Safety | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Raw Pointer (new/delete) | Manual / Unclear | None | Prone to leaks and errors | Legacy code or low-level interaction with C APIs. |

std::unique_ptr | Exclusive / Unique | None (Zero-cost) | High (Compile-time checks) | The default choice for all owning pointers. |

std::shared_ptr | Shared / Reference-counted | Yes (Reference count) | High (Runtime checks) | For shared ownership, such as in graph data structures or implementing an Observer pattern where the lifetime of the subject and observers are not strictly nested. |

Managing memory for a single thread is one challenge; ensuring safety when multiple threads are involved adds another layer of complexity.

5. Memory in a Multi-Threaded World

Memory management becomes significantly more complex in concurrent applications because all threads in a process typically share the same heap. Without proper safeguards, this shared access can lead to chaos.

5.1. The Ultimate Danger: Data Races

A data race is the most dangerous type of concurrency bug. It occurs when:

- Two or more threads access the same memory location concurrently.

- At least one of the accesses is a write.

- There is no synchronization mechanism to protect the access.

A data race results in undefined behavior. This is not just a theoretical problem; it can lead to silent data corruption, unpredictable crashes, and other hard-to-diagnose issues.

5.2. Preventing Data Races with Synchronization

To prevent data races, C++ provides two primary tools that ensure operations on shared memory are orderly and safe.

std::mutex: A mutex (short for “mutual exclusion”) acts as a lock. It ensures that only one thread can access a “critical section” of code at a time. A thread mustlock()the mutex to enter the critical section andunlock()it upon exit, allowing other threads to proceed. While you can manually call.lock()and.unlock(), using a Resource Acquisition Is Initialization (RAII) helper likestd::lock_guardensures the mutex is always released, even if an exception occurs.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

#include <iostream> #include <thread> #include <mutex> #include <vector> std::mutex mtx; // The "lock" int shared_counter = 0; // Shared resource void increment(int iterations) { for (int i = 0; i < iterations; ++i) { // The lock_guard constructor locks the mutex. // Its destructor (at the end of the loop scope) automatically unlocks it. [6] std::lock_guard<std::mutex> lock(mtx); // --- CRITICAL SECTION START --- shared_counter++; // --- CRITICAL SECTION END --- } } int main() { std::thread t1(increment, 1000); std::thread t2(increment, 1000); t1.join(); t2.join(); std::cout << "Final Counter: " << shared_counter << std::endl; }

std::atomic: Thestd::atomictemplate provides types that guarantee that operations (like reads, writes, and increments) are “atomic.” Unlike a mutex, which stops other threads, atomic operations are indivisible at the hardware level; they cannot be interrupted mid-operation [source text in prompt]. By default, atomic operations provide inter-thread synchronization, meaning astorein one thread synchronizes with aloadin another.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25

#include <iostream> #include <thread> #include <atomic> // std::atomic provides data-race-free access without a full lock. std::atomic<int> atomic_counter(0); void atomic_increment(int iterations) { for (int i = 0; i < iterations; ++i) { // This operation is indivisible and safe from data races. // It is shorthand for atomic_counter.fetch_add(1); atomic_counter++; } } int main() { std::thread t1(atomic_increment, 1000); std::thread t2(atomic_increment, 1000); t1.join(); t2.join(); // Default load() is sequentially consistent (memory_order_seq_cst). std::cout << "Final Atomic Counter: " << atomic_counter.load() << std::endl; }

By eliminating data races from your program, the C++ memory model guarantees sequentially consistent execution, meaning the result of your multi-threaded program will be predictable and reliable, as if the operations of all threads were executed in some single sequential order.

While smart pointers handle most dynamic memory needs, sometimes you need finer control over how containers like std::vector get their memory. This is the job of allocators.

6. Under the Hood: Allocators

An allocator is a component of the C++ Standard Library responsible for handling all memory allocation and deallocation requests for containers like std::vector, std::map, and std::list.

By default, all standard containers use std::allocator, which is a general-purpose allocator that simply calls the global operator new and operator delete functions. However, there are scenarios where you might want to provide a custom allocator.

There are two primary reasons for writing a custom allocator:

- Performance: For applications that perform many frequent allocations of small amounts of memory (like in a

std::listorstd::map), the default allocator can be slow and lead to heap fragmentation. A custom allocator that uses a memory pool — a pre-allocated large block of memory—can serve these small requests much faster by simply handing out chunks from the pool. - Specialized Memory: Custom allocators can encapsulate access to different types of memory, such as shared memory that needs to be accessible by multiple processes, or memory managed by a third-party garbage collector.

Knowing the theory is essential, but a skilled C++ programmer also needs practical tools and habits to diagnose problems and write robust code.

7. In the Trenches: Debugging and Best Practices

7.1. Finding Leaks and Errors with Valgrind

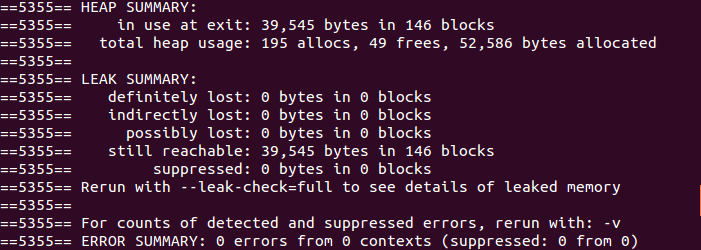

Valgrind is a powerful instrumentation framework for dynamically analyzing programs. Its Memcheck tool is invaluable for finding memory leaks and memory errors (like invalid reads and writes) in C++ programs.

Here is a simple step-by-step guide to using it:

- Step 1: Compile with Debug Symbols To get meaningful output with file names and line numbers, compile your program with debug symbols using the

ggdb3orOgflag. - Step 2: Run Your Program via Valgrind Execute your program through Valgrind with flags that provide detailed leak information.

- Step 3: Interpret the Output

- A Clean Run: A successful run with no leaks will show a “HEAP SUMMARY”.

- A Leak Report: If a leak is detected, Valgrind will show you where the leaked memory was allocated. The backtrace points directly to the

newormalloccall that is the source of the leak.

Resource: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/5134891/how-do-i-use-valgrind-to-find-memory-leaks

7.2. A Defensive Coder’s Checklist

Adopting good habits is the best way to prevent memory errors before they happen.

- Prefer Stack Allocation: If data doesn’t need to outlive the function it’s created in and isn’t excessively large, always prefer creating it on the stack. It’s faster and automatically managed.

- Embrace RAII and Smart Pointers: For all heap allocations, use

std::unique_ptrby default. Only usestd::shared_ptrwhen you are certain that shared ownership is a necessary part of your design. - Trust Nothing: Never assume function arguments are valid, especially raw pointers. Always check for

nullptrand validate inputs to prevent crashes and security exploits. - Initialize Everything: Always initialize variables when you declare them to avoid using indeterminate, garbage values. Crucially, initialize pointers to

nullptrso thatdeletecan be safely called on them even if they never end up owning a resource. This prevents a common class of errors when cleaning up objects in complex states. - Write “Boring” Code: Avoid being overly “clever” or tricky. Simple, readable, and direct code is easier to maintain, reason about, and is far less prone to subtle bugs. Make your solution fit the problem.

- Use Safe Wrappers: When interfacing with legacy C-style APIs that return raw pointers (e.g., from

malloc), immediately wrap the returned pointer in an appropriate smart pointer or a custom RAII class to ensure its lifetime is managed safely.

Conclusion

Modern C++ has transformed memory management from a manual, error-prone chore into a safe and systematic process. By understanding and applying a few core principles, you can write code that is both highly performant and exceptionally robust.

Here are the three most important takeaways:

- Scope is Your Garbage Collector: The RAII principle is the foundation of C++ memory safety. By tying the lifetime of a resource to a stack-based object, cleanup becomes automatic, predictable, and exception-safe.

- Smart Pointers are Your Primary Tool:

std::unique_ptrshould be your default choice for all dynamically allocated memory. It is safe, has no overhead, and clearly communicates the exclusive ownership of a resource. - Ownership is the Central Concept: Always be clear about which part of your code owns a resource and is therefore responsible for its cleanup. Modern C++ features like smart pointers are designed to make this ownership explicit and verifiable by the compiler.

By internalizing these principles, you can confidently wield the power of C++ to build applications that are not only fast but also safe, maintainable, and correct.