The content below are my notes for the class "16-650 Systems Engineering and Management for Robotics” Fall 2024, by Dr. Dimi Apostolopoulos. The credit for the full content goes to Professor Dimi along with several internet sources. You can see a clear relation of the below concepts with my MRSD Capstone Project, the Lunar ROADSTER – check Conceptual Design Review Report (CoDRR).

System

Definition

A system is an arrangement of parts or elements that work together to exhibit behavior or meaning that is not obtainable by the individual elements alone. It can be physical, conceptual, or a combination of both.

Key aspects of a system include:

Interconnected elements: A system comprises multiple components that interact with each other.

Purposeful arrangement: The elements are organized in a specific way to achieve one or more stated purposes.

Emergent properties: The system exhibits behaviors or characteristics that cannot be attributed to any single component.

Boundaries: Systems have defined boundaries that separate them from their surroundings.

Inputs and outputs: Systems typically receive inputs, process them, and produce outputs.

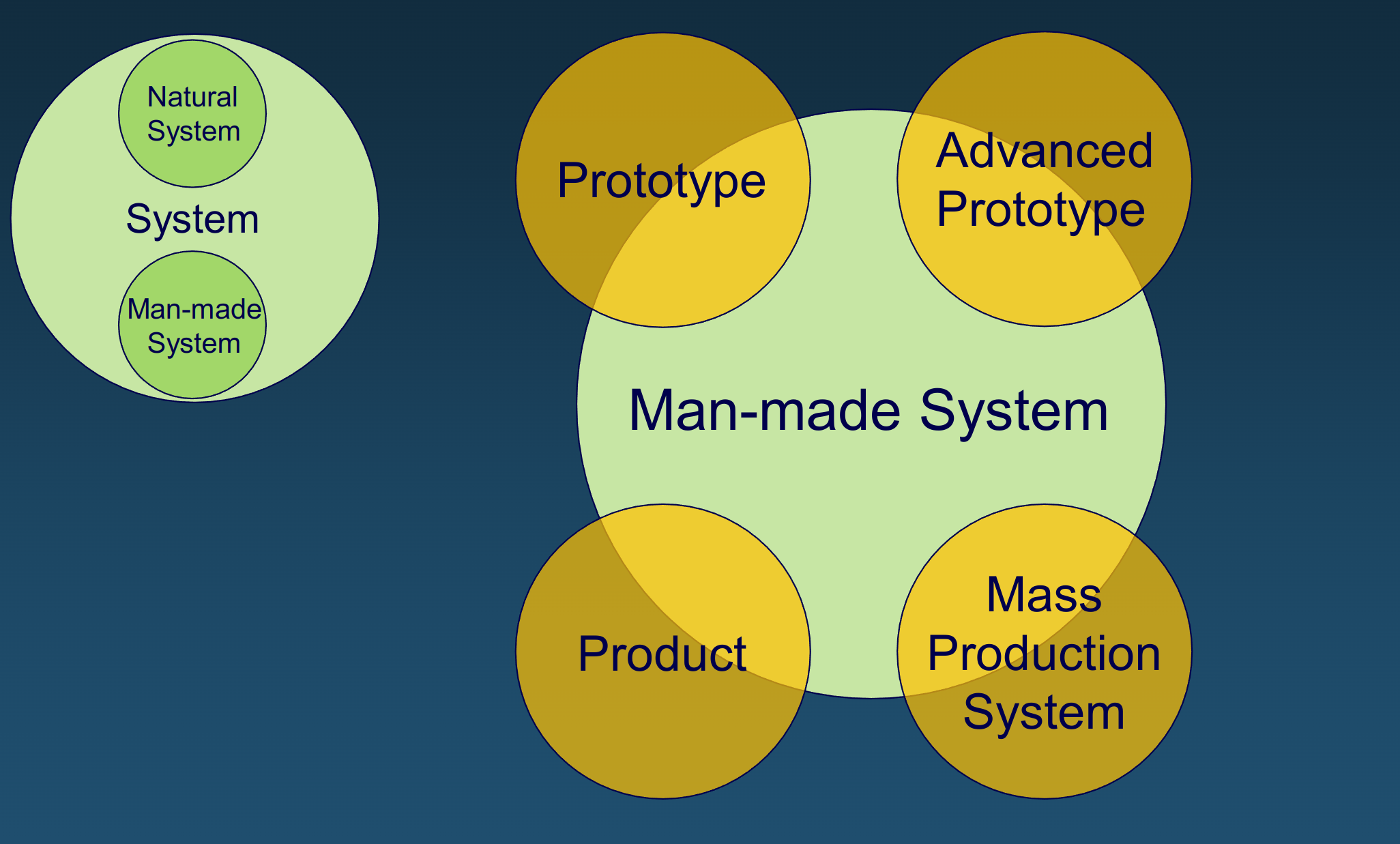

System vs Product: A product is a system that has been specifically designed, developed, and packaged to meet user needs and be offered in the market. It is typically a refined and polished version of a system.

Common Characteristics of Man-Made Systems:

Complexity: Man-made systems are typically complex, consisting of multiple interconnected components that work together to achieve a specific purpose.

Interdisciplinary Nature: These systems often require expertise from various fields of engineering and other disciplines to design, develop, and maintain.

Evolutionary Nature: Man-made systems tend to evolve over time, with updates, improvements, and adaptations to meet changing requirements or technological advancements.

Team-Based Development: They are usually created and managed by teams of professionals with diverse specialties, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of the systems.

Formal Systems Engineering Approach: The development and management of these systems typically follow structured systems engineering processes and methodologies.

Meta System: Multiple systems can work together to form a "System of Systems", whose results cannot be obtained by a single system.

What do Systems Entail?

Hierarchy: Systems often have layered structures with subsystems and components.

Attributes: Characteristics of system elements, including functional and non-functional properties.

Relationships: Interconnections and interactions between system elements.

State: Condition of an element or the entire system at a specific point in time.

Behaviors: Describes how the sequences of element states and system responses change over time.

Processes: Sequence and timing of behaviors.

Significance of Top-Down Representation of a System:

Top-down representation involves starting with a high-level view of the system and progressively breaking it down into its constituent parts. Its importance:

Comprehensive Understanding: It provides a holistic view of how all components interact within the system, facilitating better comprehension of the overall functionality.

Effective Problem-Solving: By identifying the system’s structure, potential issues can be localized more efficiently, allowing for targeted interventions.

Enhanced Planning: A top-down approach aids in organizing tasks and allocating resources effectively by establishing clear priorities and dependencies among components.

Improved Communication: This method simplifies the explanation of complex systems to stakeholders by presenting information in a logical and structured manner.

Design Flexibility: Changes can be implemented at lower levels without necessitating a complete redesign of the entire system, thus promoting adaptability.

Functional vs Non-Functional Attributes

Functional Attributes:

Define what the system or software shall do - specific functionalities and features.

Specified by users/customers.

Describe system behavior and functions that it should perform during operation.

Captured in use cases.

Mandatory to implement.

It refers to the system as a whole.

Non-Functional Attributes:

Define how the system should perform or behave - quality attributes.

Specified by technical teams (architects, developers).

Describe system properties and constraints.

Captured as quality attributes.

Not always mandatory, but impact overall quality.

Some non-functional attributes can include:

Physical parameters - Size, weight, speed, range, accuracy, flow rate, throughput, etc.

Deployment and distribution - Geographic deployment locations; Quantity of personnel, equipment, facilities, etc. at each location

Life cycle horizon - Who will operate the system? For how long? What inventory of parts do I need to maintain?

Utilization - How many hours/day, days/week, weeks/year will be the system be used? How many operational cycles/period? How will users interact with the system?

Effectiveness - Availability, mean time between failures, maintenance downtime, operator skill level

Environmental - Temperature, humidity, altitude, Airborne, ground, underwater

Interoperability with other systems

Key differences:

- Functional requirements specify "what" the system does, while non-functional requirements specify "how" it does it.

- Functional requirements are usually visible to users, while non-functional requirements are often behind-the-scenes qualities.

Systems Engineering

It focuses on defining customer needs and required functionality early in the development cycle, documenting requirements, and then proceeding with design synthesis and system validation while considering the complete problem: operations, cost and schedule, performance, training and support, test, manufacturing, and disposal.

Distinctions of systems engineering:

Top-down, holistic approach: Views the entire system before examining individual parts, considers system-wide goals and requirements first, and ensures cohesive integration of all components.

Focused on the what, not the how: Defines system requirements and capabilities, and avoids prescribing specific implementation methods.

Life-cycle oriented: Considers all stages from conception to retirement, addresses long-term sustainability and adaptability, plans for maintenance, upgrades, and eventual disposal.

Interdisciplinary: Integrates knowledge from multiple fields, facilitates collaboration between different specialists, ensures comprehensive consideration of all system aspects.

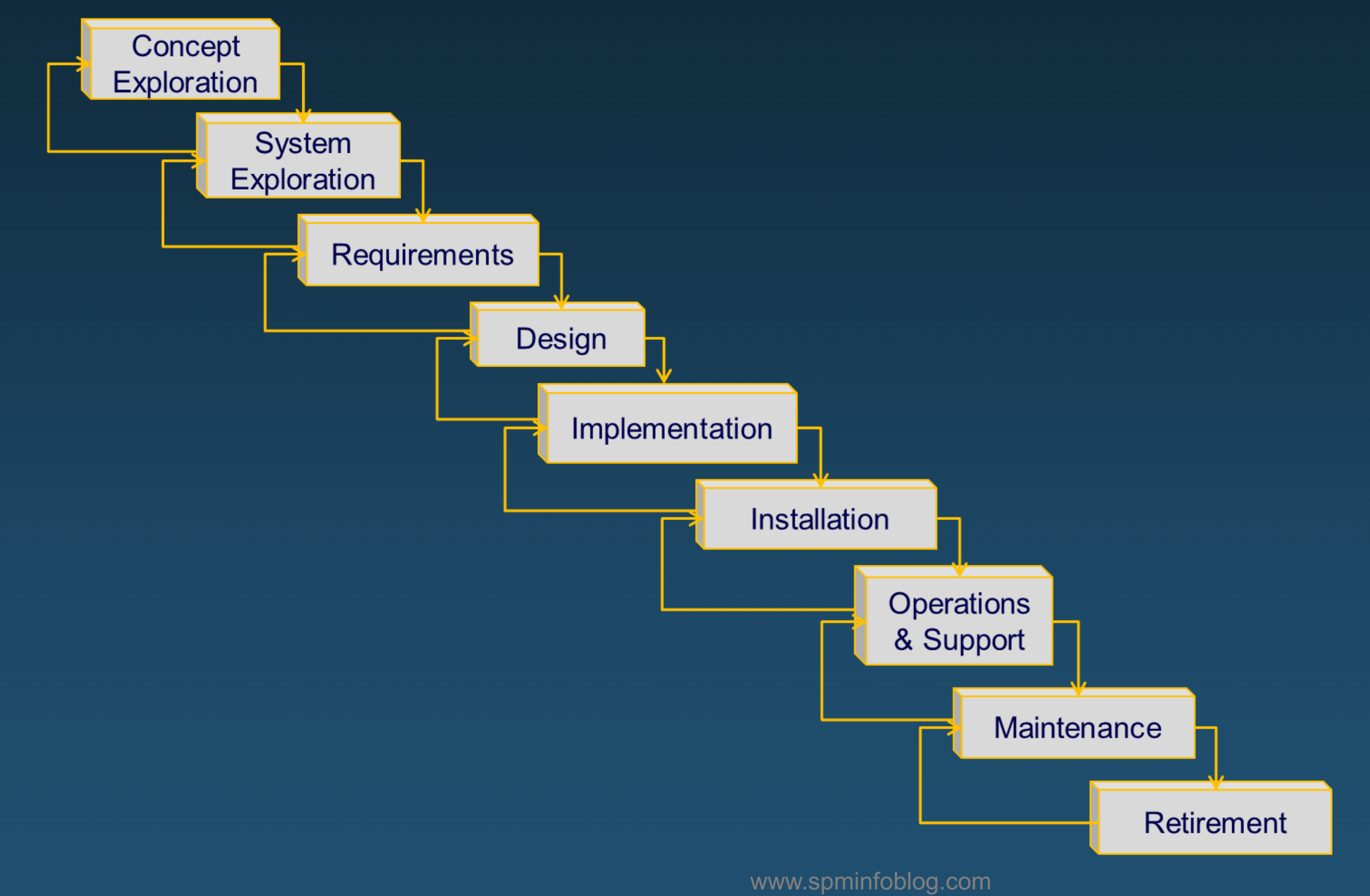

Waterfall Model

All major phases of design and engineering happen sequentially

Each phase is distinct

There is no iteration between phases

Requires careful planning and execution

Each phase must be carried out in great detail and address potential risks

Effective if requirements are well defined, budget allows for complete development cycles, and prior similar developments exist

Not suitable for large projects and brand new systems subject to evolving requirements

REQUIREMENTS CAPTURE $–>$ DESIGN SYSTEM $–>$ BUILD SYSTEM $–>$

DEVELOPMENTAL TESTING $–>$ ACCEPTANCE TESTING $–>$ SYSTEM FIELDED AND IN USE

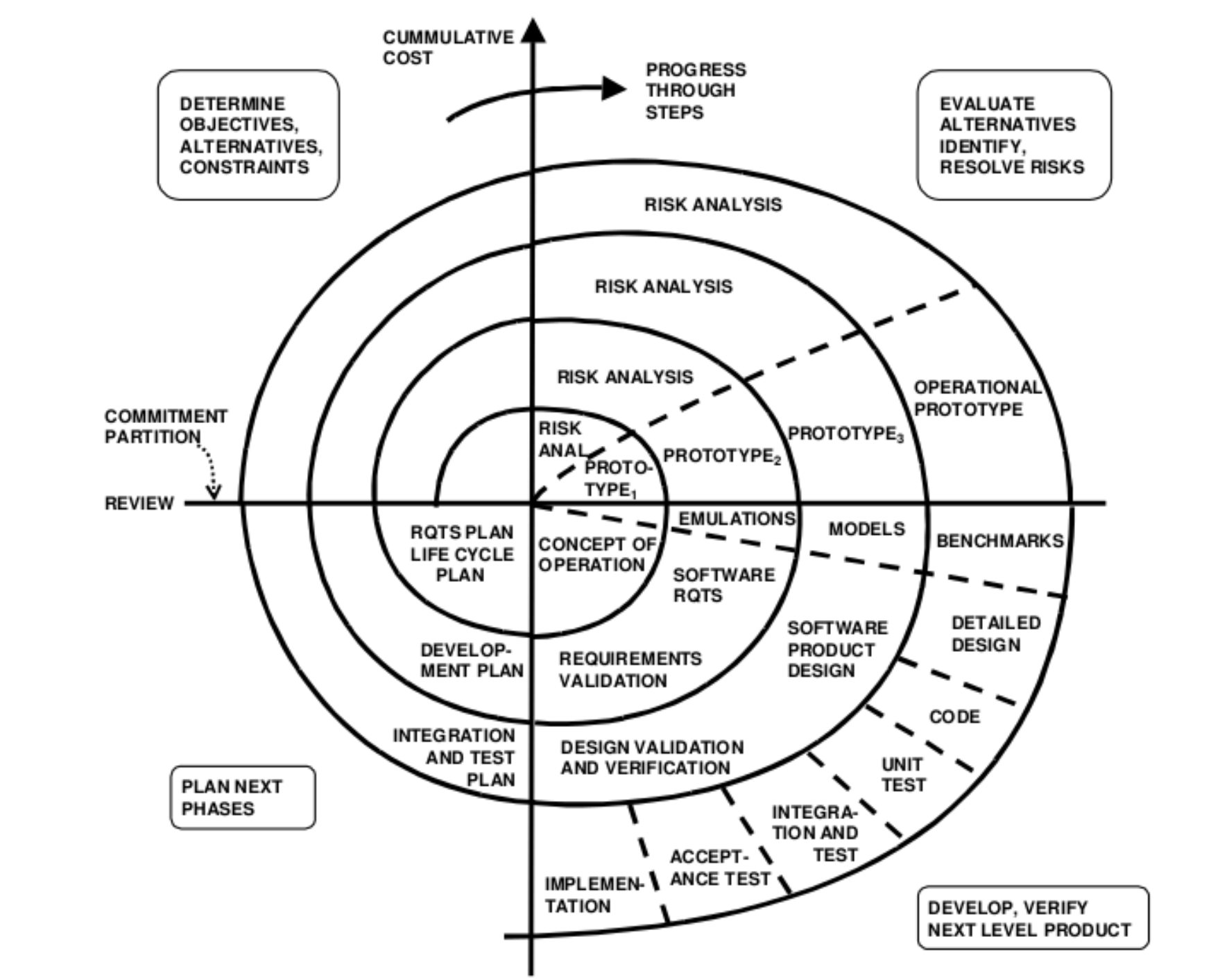

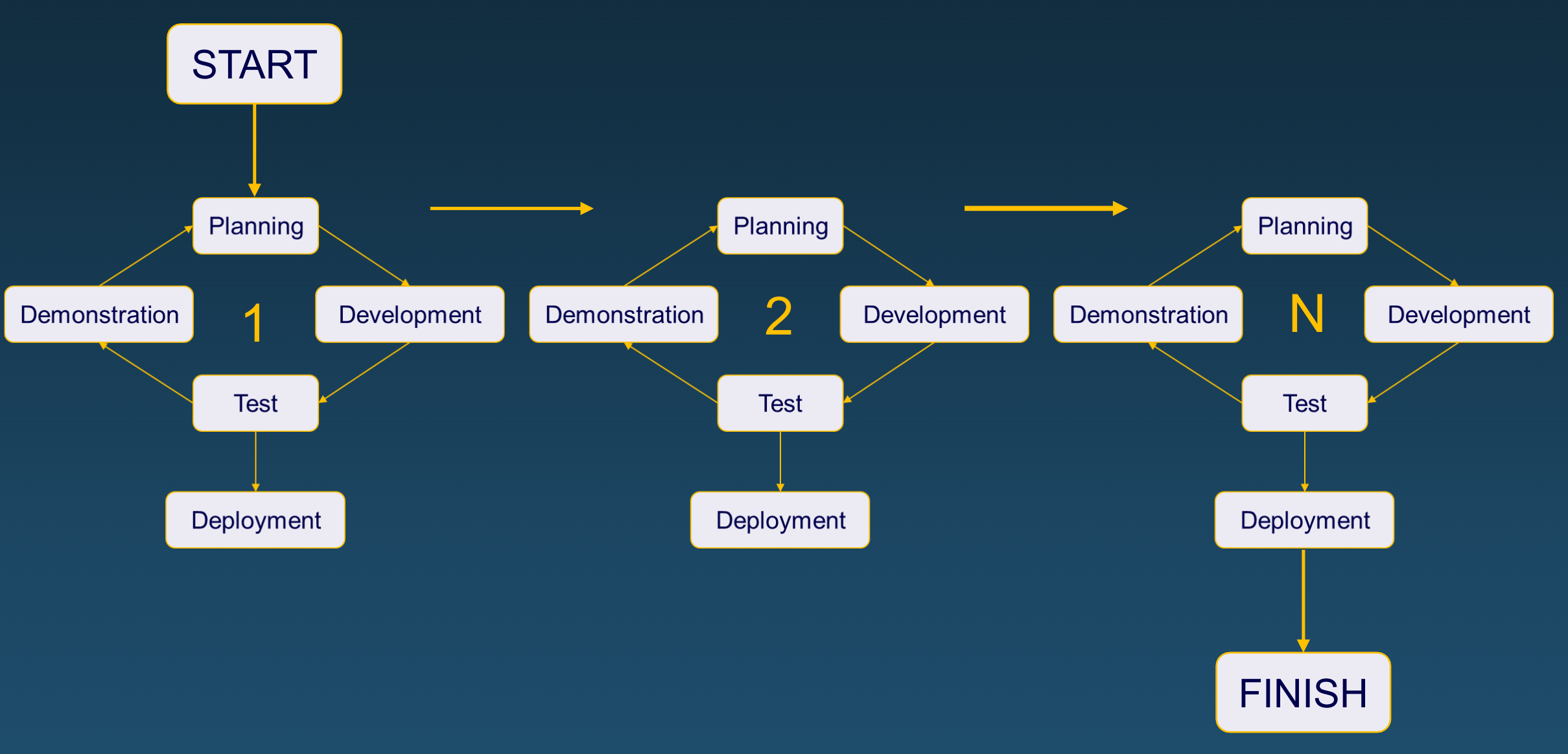

Spiral Model

Four major phases

Iterative process

Multiple waterfalls with feedback

System matures with each iteration

Various prototypes

Prototyping follows risk identification

More suitable for large projects and large budgets, handles changing requirements, customers can use interim versions of system

Complex to plan and execute, high cost, risks must be identified correctly

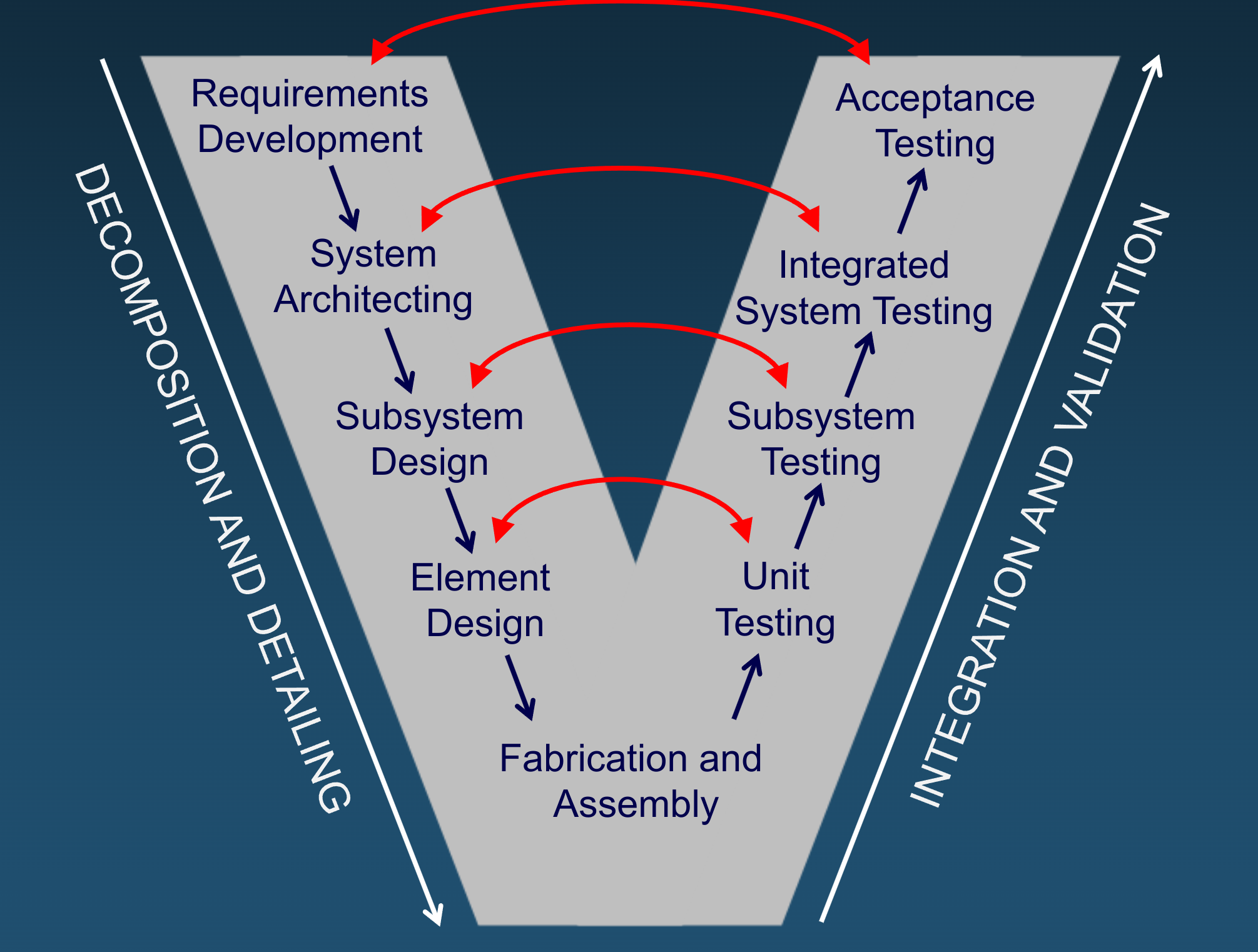

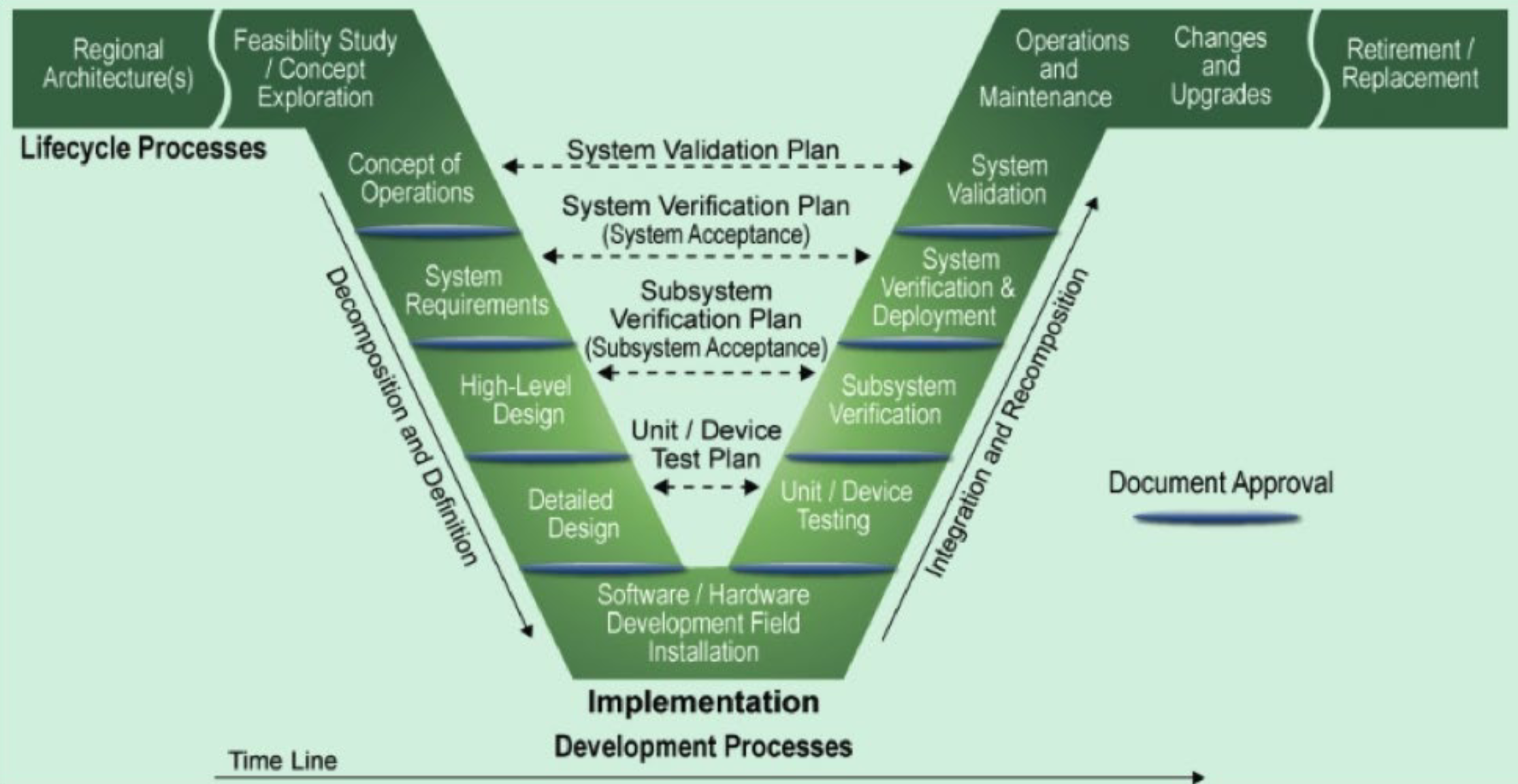

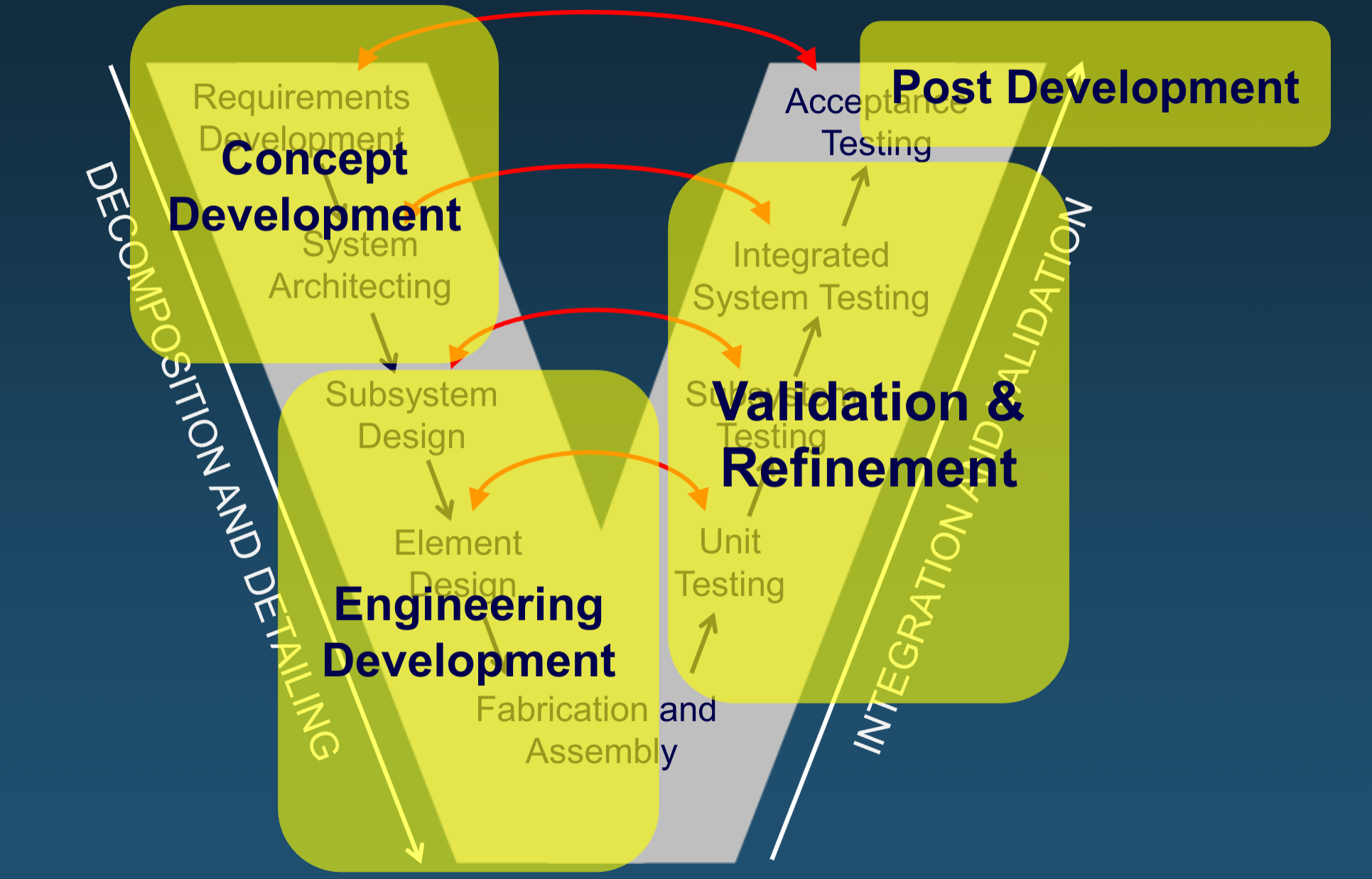

V Model

Left side of V: Requirements, architectures, design; from higher-level to detailed

Bottom of V: Build, fabrication, assembly, prototyping, initial integration

Right of V: Full integration, testing, validation, acceptance; from small unit testing to full-system testing and acceptance

Testing matches level of system hierarchy, e.g. element design requirements are validated at the unit testing level, subsystem design requirements are validated at the subsystem level, etc.

Encourages careful definition of requirements and architectures upfront. Detailed execution of the early stages is critical to the success of the system and project

Facilitates deliberate testing, debugging, and validation of smaller system elements before escalating to larger elements

Any change in requirements must be handled by a thorough review of architecture and design and, if necessary, re-architecting and re-designing

Since no early system prototypes are built, one must follow process in completing the testing and validation steps thoroughly to ensure compliance to requirements

For larger, more complex systems and projects we apply the V method in applied R$\&$D.

Agile Model

Incorporates both incremental and iterative methods

Emphasizes flexibility and adapting to changing priorities

Uses short iterative cycles with frequent demonstrations and user feedback

Focuses on continuous delivery of value and customer satisfaction

Better suited for projects with high uncertainty or changing requirements

For retrofits-for-automation and subsystem R$\&$D we apply agile methods.\

What is the difference between Spiral model and Agile model?

The spiral model is more structured, relies heavily on risk analysis, and is best suited for larger, more complex projects. It balances planning and prototyping with iterative development.

The agile model is more flexible, emphasizes on frequent delivery of working software, and continuously involves customer interaction. It is best suited for projects that need to quickly adapt to changing requirements.

Key Considerations when Choosing a Systems Engineering Model

Treatment of Requirements: Decide between defining all requirements upfront or using an iterative approach.

Attributes of System: Assess if the system is new, modified, or retrofitted, and its size (small, medium, large).

Budget and Time Constraints: Evaluate available funding and project timelines for system delivery.

Technical Expertise and Organizational Capabilities: Consider the skills of the team and the maturity of organizational processes.

Treatment of Risk: Determine if the design will focus on risk mitigation and how to handle uncertainties.

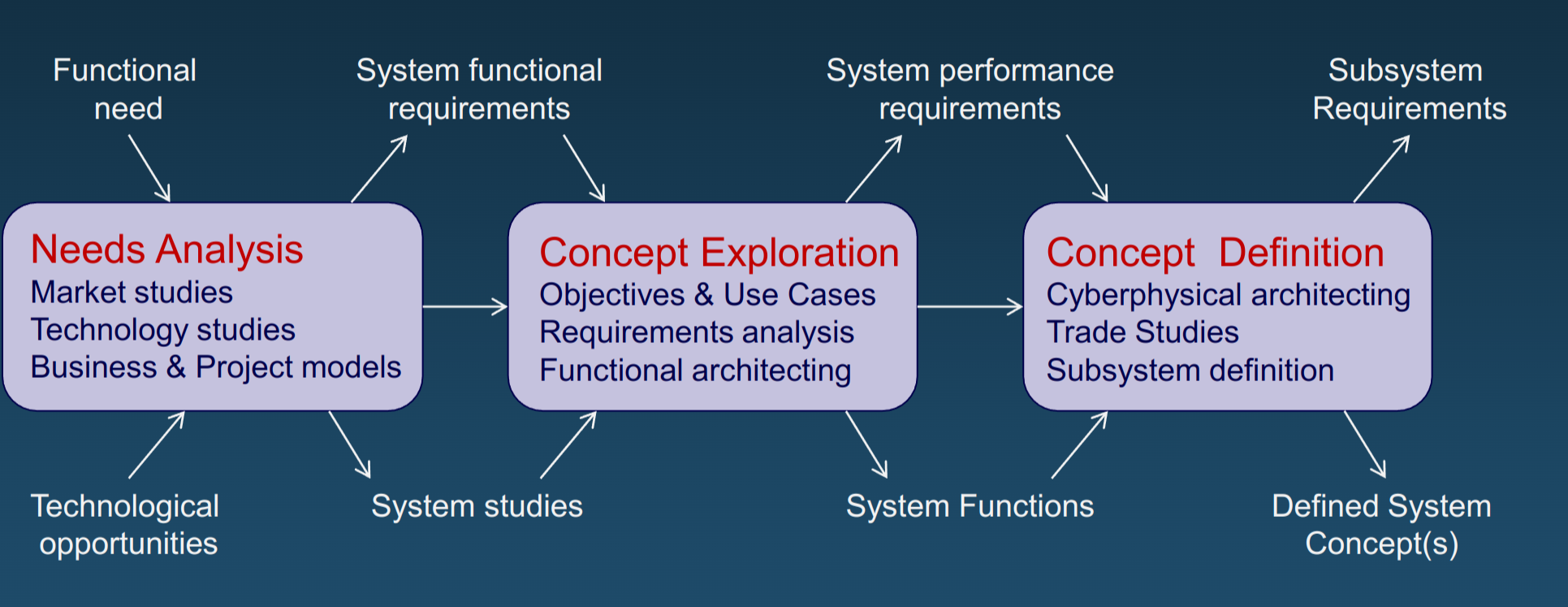

Concept Development Phase

It is the first phase of the system life cycle. Its key commitments are:

Function: Defined in the Functional Architecture

What the system needs to do

Capabilities and behaviors

Form: Captured in the Cyberphysical Architecture

How the system will be physically realized

Hardware and software components

Its main purposes are to:

Develop detailed conceptual designs

Conduct trade studies to evaluate alternatives

Make important subsystem-level decisions

Formulate approach for system development

Outline project management strategy

It sets the foundation for the entire project and bridges the gap between high-level needs and concrete system concepts.

Needs Analysis

Study, analyze, and assess:

Study Market and Technology

Data gathering: Collect relevant information

Market analysis: Understand current market conditions and trends

Techno-economic feasibility: Assess technical and economic viability

Analyze Need

Socio-economic objectives: Identify broader societal and economic goals

Functional/operational objectives: Define specific system functions and operations

Key performance measures: Establish metrics to evaluate system success

Assess Technology

New or improvement: Determine if developing new technology or improving existing

State-of-art: Evaluate current technological landscape, identify areas for improvement or innovation, set standards for comparison

Patents: Review existing patents to avoid infringement and identify opportunities

Concept Exploration - Requirements Analysis

Requirements translate stakeholder needs into specific, actionable criteria for system design and development. Systems must comply to specific requirements. They should describe the "what", not the "how", and must be unambiguous.

Types and classification of Requirements:

User requirements (needs, musts, wishes, wants...)

System requirements (some user, some derived) - Functional/Performance requirements, Non-functional requirements

Mandatory (threshold) and desirable (stretch, objective)

Hardware and software subsystem requirements

Interface requirements

The life cycle of Requirements are:

Elicitation (seek, extract)

Development (formulate, write, edit) system, functional/non-functional

Analysis (allocate, prioritize) subsystem, threshold/objective

Tracking

Validation

Revision

Performance Requirements: They define how well the system should perform its functional requirements and meet its capabilities. Key features include:

Quantitative nature: They are measurable and expressed in specific, numerical terms.

Minimal quantitative baselines are set, and can also include "stretch" goals for exceptional performance.

They specify the level of performance for each functional requirement.

They are reviewed and refined throughout concept development and possibly engineering development phases.

Functional requirements start with Shall

Performance requirements start with Will

Non-functional requirements start with Will

Elicit Requirements

Where do the requirements come from? These are some of the ways by which requirements can be elicited:

Learn from users, customer, sponsor

Learn from the application

Study operational documents

Study design documents

Examine state-of-art and relevant designs

Review market studies

Review technology studies

etc.

While eliciting requirements, it is important to keep in mind the type of system, such as new, upgrade or retrofit, and whether the system is built for a user or stakeholder.

User vs Stakeholder: Users directly interact with the system on a daily basis and have firsthand experience with the system functionality and usability. They are responsible for operating, maintaining, and managing the system.

Stakeholders are a broader group with interest or influence in the system. They can include users, but can also be non-users with some interests in the system. They may not directly use the system but are affected by its outcomes.

Key difference between User and Stakeholder:

All Users are Stakeholders, but not all Stakeholders are Users.

Stakeholders typically impose design constraints: Cost and schedule limitations; Standards, policies, and procedures to follow; Safety and security requirements; Performance specifications; System qualities (e.g., reliability, maintainability).

While Users provide valuable insights into day-to-day system operation, Stakeholders shape the broader context and constraints within which the system must function.

Elicitation for a Novel System

When we’re trying to figure out what a brand new system should do, we face both good things and tricky parts:

Good Things:

Big Picture Thinking: It’s easier to talk about what the system should do in general terms. We’re not stuck with old ideas.

Blank Canvas: We can design the system however we want. There’s no old system holding us back.

New Ideas Welcome: We can use the latest tech and come up with fresh solutions.

Tricky Parts:

No Users Yet: We might not have actual users to ask about what they need.

Unfamiliar Territory: People aren’t used to this kind of system, so they might struggle to tell us what they want.

Seeing the Whole Picture: It’s hard to think of everything the system needs to do when it’s all new.

Unclear Connections: We might not know how different parts of the system should work together at first.

No Instructions: There are no old manuals or documents to look at for guidance.

What to Keep in Mind:

Focus on what the system needs to achieve, not specific features yet.

Use models or demos to help people imagine the system.

Look at what similar products do and what people like or dislike about them.

Brainstorm a lot and think about different situations where the system might be used.

Be ready to change your ideas as you learn more.

Note: When working on a completely new system, it’s important to be creative and flexible. Keep talking to people who might use or be affected by the system, and don’t be afraid to change your plans as you go along.

Elicitation for Retrofitting/Upgrading a System

Good Things:

Experienced Users: People have used the system and know it well. They can tell us what’s good and what needs fixing.

Real System to Look At: We can see and work with the actual system. This helps us understand how it works and what needs changing.

Existing Documentation: There are usually manuals or guides about the system.

Tricky Parts:

Limited by Old Design: The current system might restrict what we can change. We might have to work around existing parts or features.

Outdated Tech: The system might use old technology. This can make it hard to add new, modern features.

Too Many Rules: The existing system might have lots of requirements that we have to follow. This can limit how much we can change things.

User Bias: People used to the old system might resist big changes. They might prefer familiar features, even if they’re not the best.

What to Keep in Mind:

Listen to users, but also think about new possibilities they might not have considered.

Look for ways to improve the system while keeping what works well.

Check if old documents are still accurate before relying on them.

Balance keeping familiar features with introducing helpful new ones.

Consider if some parts of the system need a complete overhaul rather than just an upgrade.

Note: Upgrading an existing system means working with what’s already there. It’s about finding the right balance between keeping what works and making important improvements.

Methods and Techniques to Elicit Requirements:

- Objectives Tree

- Use Cases

- Surveys/Questionnaires

- Focus Groups

- Interviews

- Prototyping etc.

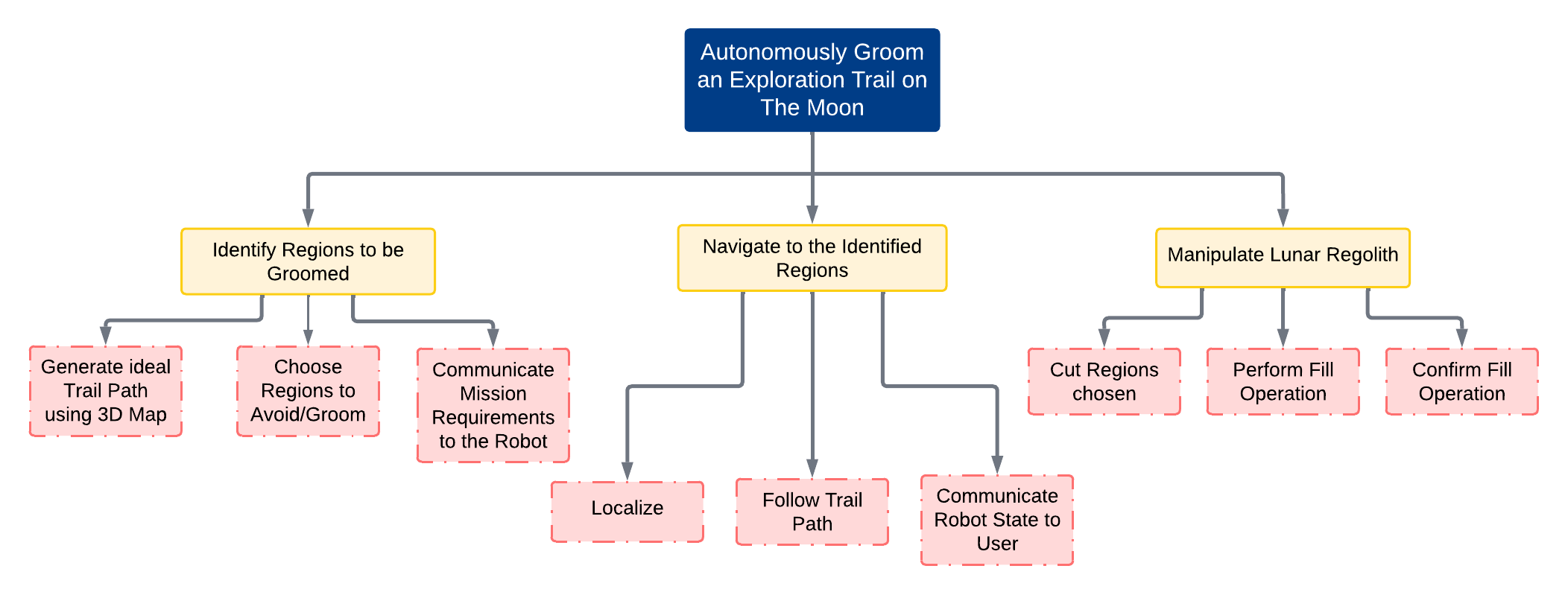

Objectives Tree

An Objectives Tree is like a family tree, but for our project goals. It helps us organize what we want to achieve, from big ideas down to specific tasks. It’s a great way to make sure everyone understands the big picture and their part in it. Key features of objectives trees are:

Top-Down Structure: Starts with our main goal at the top, then branches out into smaller objectives. The objectives become more specific as we go down the tree.

Breaks Down Big Goals: Takes our big idea and splits it into smaller, manageable pieces.

Shows Relationships: We can see how different objectives connect to each other. This helps us understand which tasks support which goals.

Use Cases

Use Cases are like stories that explain how people will use a system to get things done. They’re really helpful when designing new systems or improving old ones. They’re a great way to make sure everyone understands what the system needs to do, without getting lost in technical details too early. Key features of use cases are:

Collection of Scenarios: They’re a bunch of examples showing how the system will be used. Think of them as "day in the life" stories of system users.

Goal-Focused: Each Use Case shows how the system helps achieve a specific goal or task.

Multiple Cases Needed: Complex systems need several Use Cases to cover everything.

Not About How, But What: Use Cases describe what the system does, not how it does it.

Communication Tool: They help designers and customers understand each other better.

How should the use cases be written?

We should focus entirely on the user and what they want to do instead of the system doing things.

The title should be what the goal is or what the user wants to achieve.

Clearly define the "actor" that desires the goal. This could be a person or an interfacing system.

Write about what should happen when everything goes right. Don’t worry about the failure cases.

Narrate the story in such a way that both technical and non-technical people can readily understand it.

It doesn’t matter if a step is done by a person, software, or machine.

Concept Definition - System Architectures

System Architecture is like creating a blueprint for a complex machine or process. It’s important because it helps us understand how everything works together. It shows where you’re going, how all the parts connect, and helps everyone work together more smoothly. It’s a tool that makes complex systems easier to understand, build, and manage.

It captures the flow of functions and relationships and captures break-down of systems from top to down. There are two mains types of system architectures:

Functional Architecture

Cyberphysical Architecture - Cyber (software) + physical (hardware)

The cyberphysical architecture is derived from the functional architecture.

Difference between Functional Architecture and Cyberphysical Architecture:

Functional architecture describes what the system shall do, i.e., the functions and attributes of the components of the system. It focuses on the logical components and their interactions. They are typically represented using functional block diagrams.

Cyberphysical architecture describes how the system will be physically realised. It focuses on the physical, hardware and software components. They are typically represented by system block diagrams.

Functional Decomposition Method

It comprises of two main steps:

Identify the functions carried out by the system

Apply different ways to logically connect functions

Key points to keep in mind while developing a functional architecture:

The functions are identified by needs analysis and eliciting requirements using objective trees, use cases, etc.

It is essential to have formulated the functional requirements before developing the functional architecture.

Apply different ways to logically connect the functions.

Capture the "what", not the "how".

Think of transformation of material, information and energy.

Start synthesizing architectures assuming little or no sharing of functions among subsystems.

Deciding on connectivity and flow for our architectures is critical to what our system will be.

Include only what is needed and makes sense. It can be reiterated during the concept development phase.

Morphological Charts

Morphological charts aid in concept synthesis by:

Breaking down the system into key functional attributes

Explore different possible solutions for each function

Allowing systematic exploration of different combinations of solutions

Their significance:

Encouraging creative thinking and innovation

Providing a structured approach to generating diverse system concepts

Facilitating the identification of novel combinations that might not be immediately obvious

Supporting a comprehensive exploration of the solution space

Trade Studies

It is a systematic and structured process for comparing and selecting among different alternatives or options for a system design or solution. It is used to inform decisions by methodically framing the trade space and systematically evaluating alternatives. They help balance multiple, often conflicting criteria to find the best overall solution.

Weighted Objectives Method: It is a specific technique used within trade studies and involves assigning numerical values to features or alternatives based on predefined criteria. Each criterion is given a different weight based on its importance.

How to perform?

Identify and list all possible options

Define relevant criteria

Assign numeric weighting values to each criterion (ensure weights total to 100)

Score each option against the criteria (e.g., on a scale of 1-5 or 1-10)

Calculate weighted scores by multiplying the score by the weighting value

Sum up the total score for each option

Compare the results to identify the best alternative

What are the evaluation criteria and weighting factors?

Evaluation criteria:

Performance requirements

Non-functional requirements

Life-cycle parameters (cost, reliability, sustainability, etc.)

Technical specifications (manuals, product reports, etc.)

Weighting factors:

Customer priorities, market pull, technology push, etc.

Team and project specific prioritization

Requires a lot of communication with the stakeholders

Significance:

Provides a structured, objective approach to decision-making

Allows for consideration of multiple factors with varying importance

Helps justify decisions with quantitative data

Useful for complex decisions with multiple stakeholders

Can be applied to various fields including systems engineering, product management, and project planning

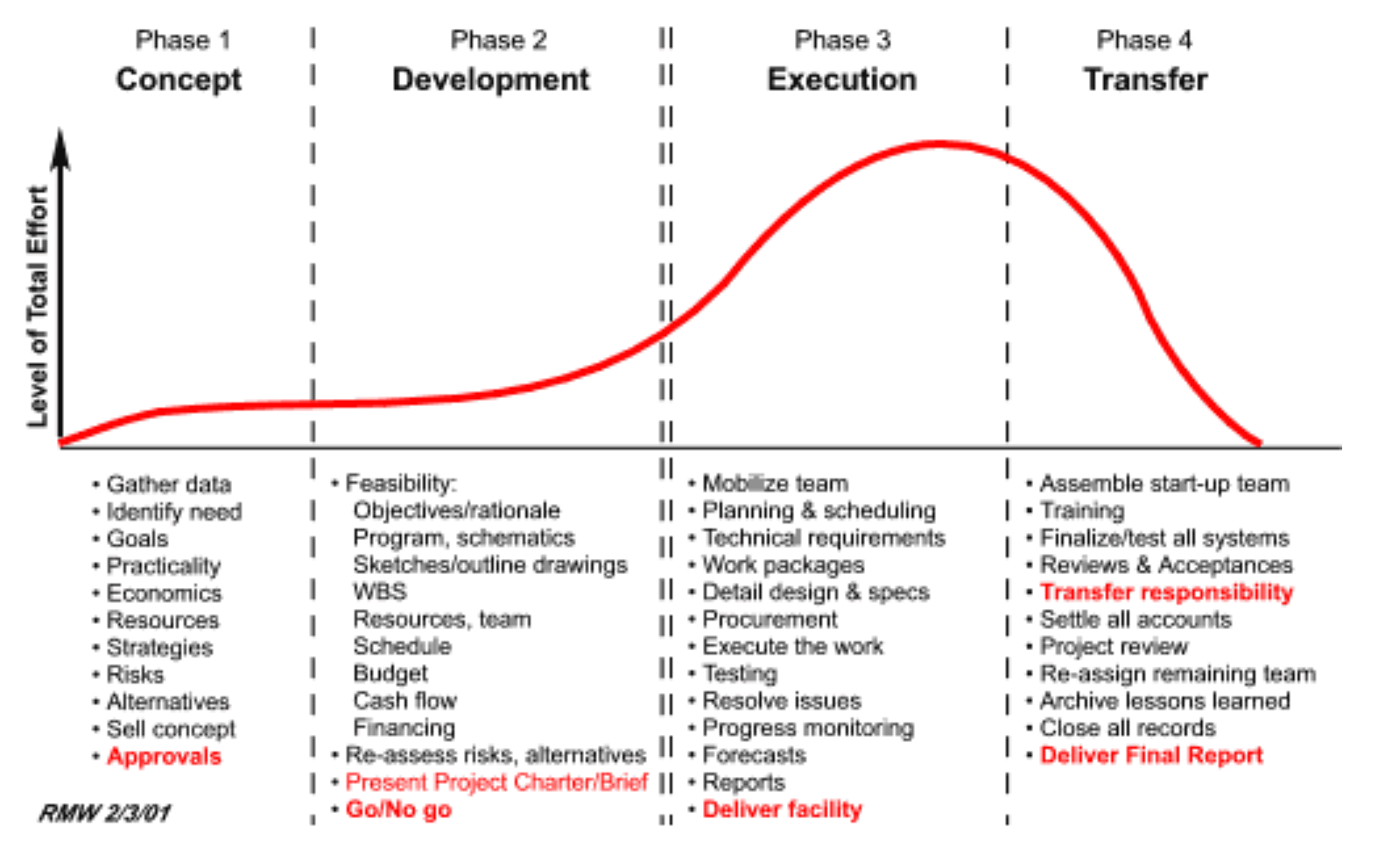

Project Management

Introduction

Project management is the application of knowledge, skills, and techniques to execute projects effectively and efficiently. It’s a strategic competency for organizations, enabling them to tie project results to business goals — and thus, better compete in their markets.

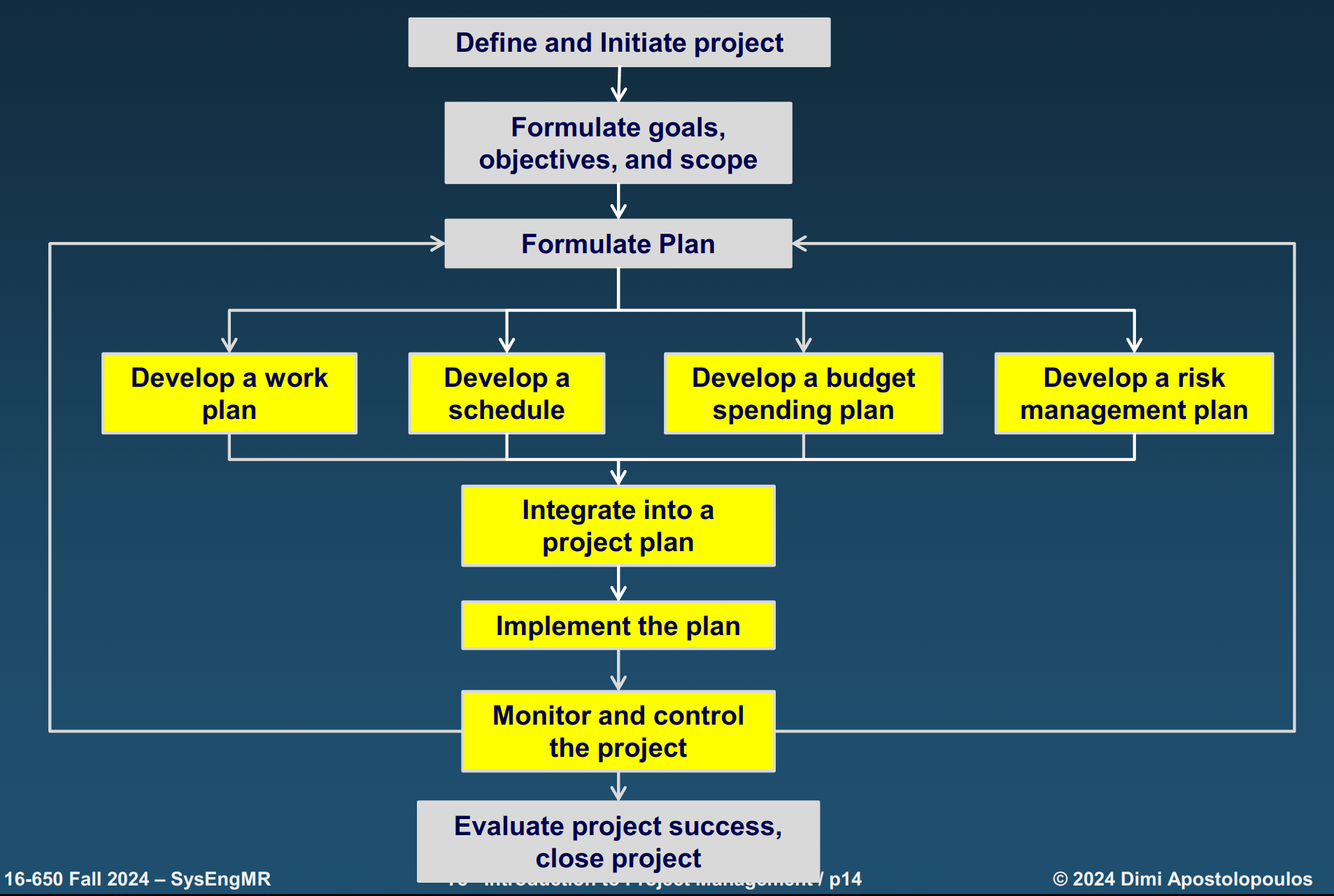

Perspective Model

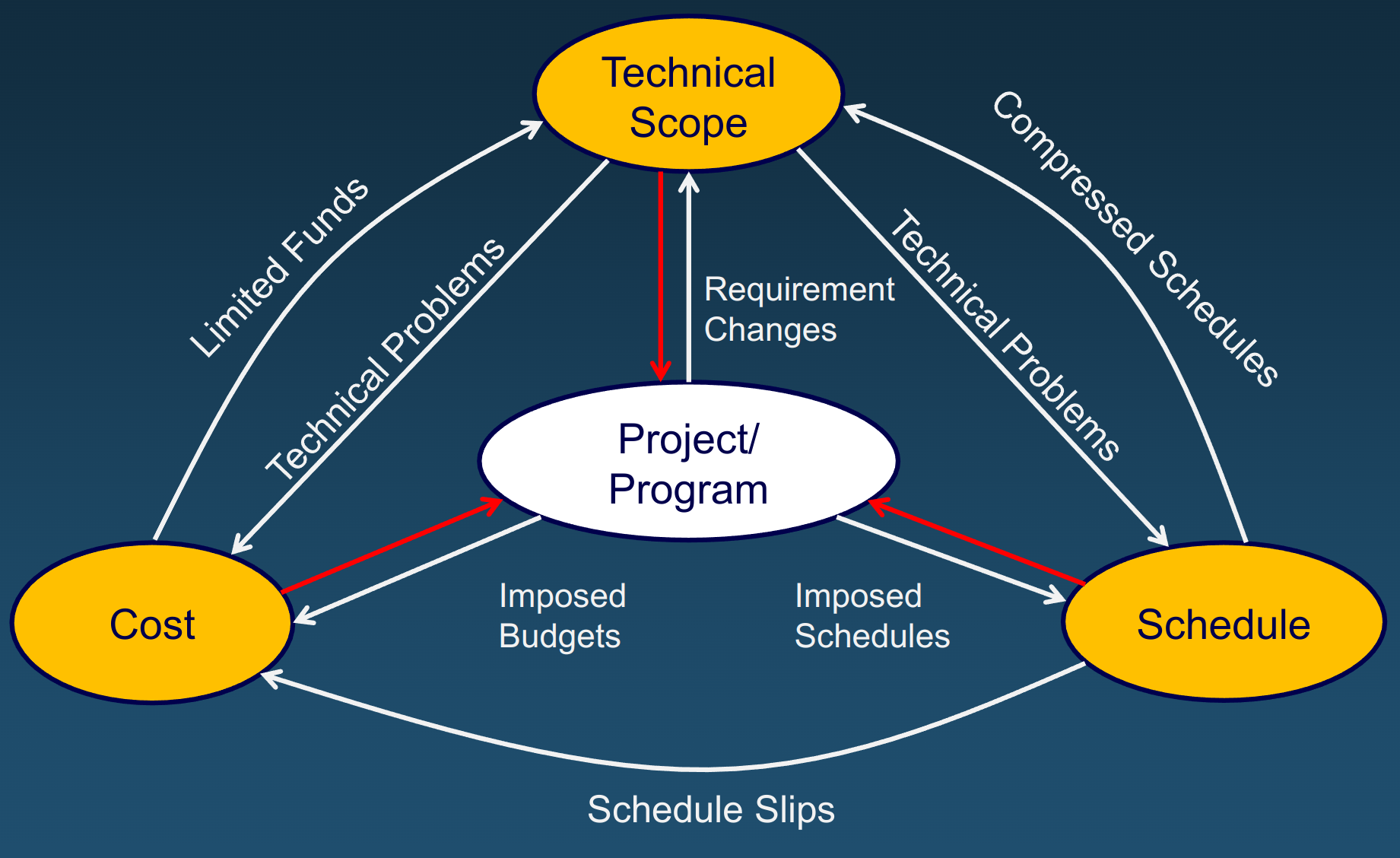

The Perspective Model for Project Management, as depicted in the image, outlines a systematic, structured approach to managing projects from initiation to closure.

How does this translate to the V-model of systems engineering?

The perspective model starts by defining and initiating the project, and formulating its goals, objectives and scopes. This is translated to V-model’s focus on developing requirements.

In the Perspective Model, detailed work plans, schedules, budgets, and risk management are created. This aligns with the V-Model’s decomposition and detailing phase, where system architecture and subsystem designs are detailed.

The Perspective Model implements the plan, while the V-Model transitions to fabrication and assembling elements.

The Perspective Model monitors progress, comparable to the V-Model’s integration and validation phase, which tests elements, subsystems, and the entire system. This stage involves proper tracking, evaluating, iterating, and replanning if necessary.

Both models conclude by ensuring the final output meets the initial objectives—Perspective Model through project evaluation and closure, and V-Model through acceptance testing and system validation.

Systems engineering is concerned with a top-down system-oriented life cycle. Project management is concerned with a bottom-up project-focused life cycle.

Initiating a Project

In order to obtain formal authorization to start the project, the following major initiation/formulation documents are required:

Statement of Work - Discusses the work to be accomplished, input requirements, work not to be accomplished, and specific results and deliverables.

Technical Proposal - Details the technical approach and methodologies

Management Proposal - Outlines team structure, schedule, and risk management

Cost Proposal - Breaks down project costs and budget allocation

Develop a Work Plan

A top-down breakdown of the work needs to be performed. This should be done in levels as:

Level 1: Total scope, system, product

Level 2: Sub-projects, subsystems, project activities; Technical, management, facilities, etc.

Level 3: Functions, activities, major tasks, assemblies/components

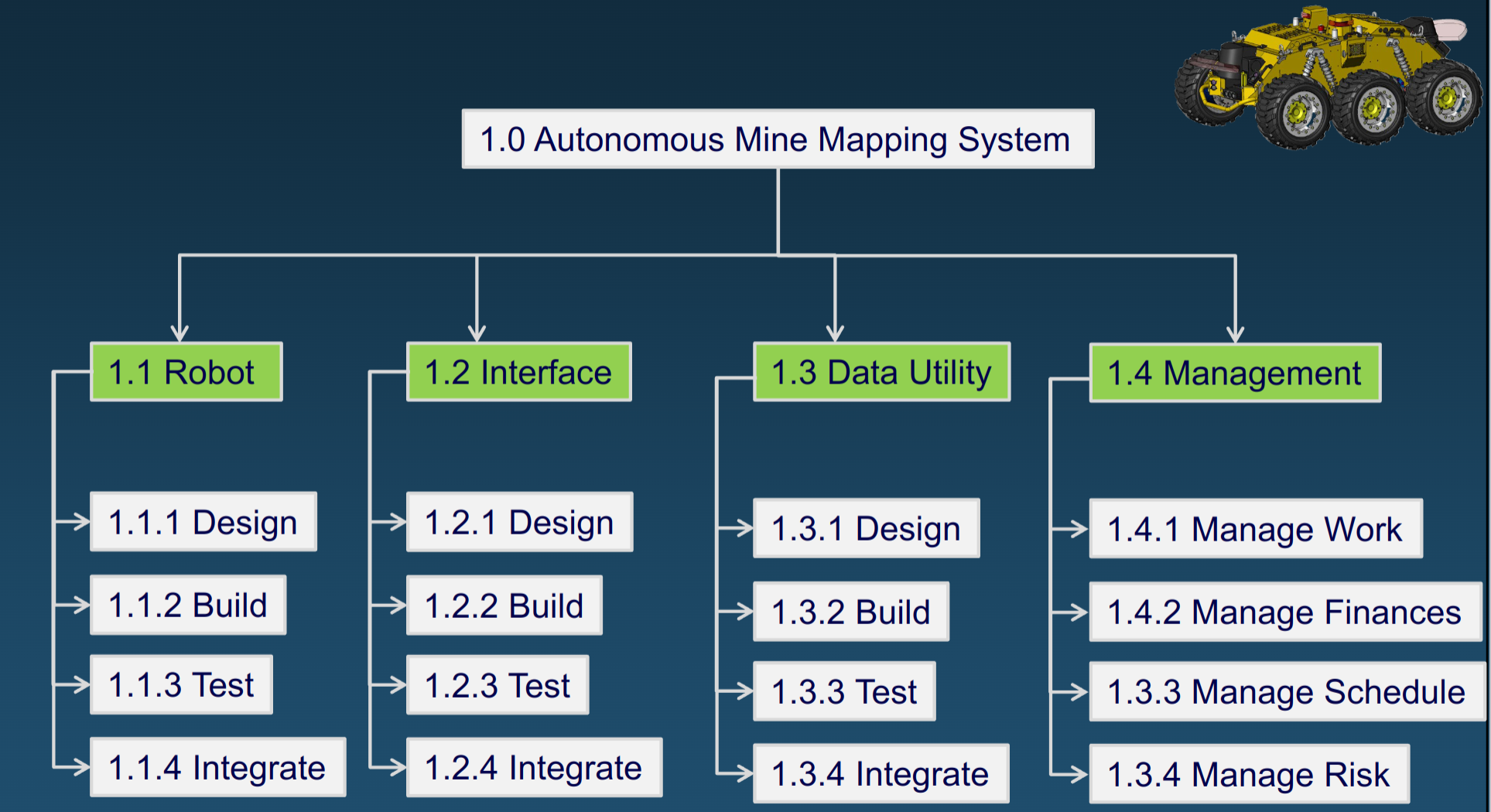

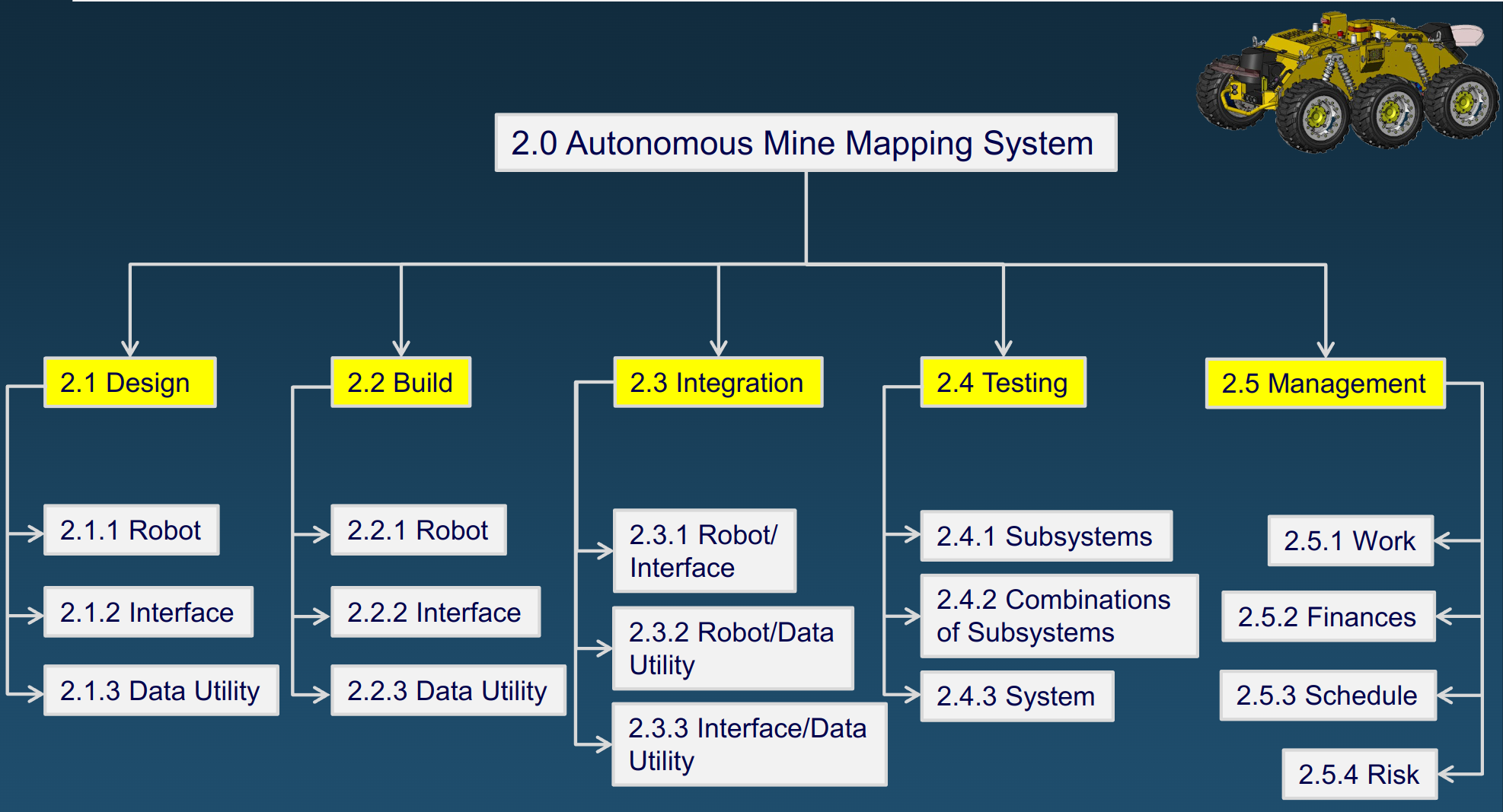

Work Breakdown Structure

The WBS is a tool to break down the total scope of a project into smaller, manageable components. It provides a structured view of what needs to be done, facilitating planning, assigning tasks, tracking progress, and managing resources. The WBS helps ensure that no important tasks are overlooked, and it provides clarity on how each task fits into the overall project.

Product-Oriented WBS:

Focus - The breakdown is based on the product or service being created or delivered. This approach organizes work around the product’s features, components, and deliverables.

Structure - Focuses on specific product components or sub-systems that need to be built or created.

Advantages - It makes the product features clear and shows how individual components fit together. It focuses on product outputs, so progress can be tracked by evaluating the completion of product components.

Process-Oriented WBS:

Focus - Focuses on the processes or phases required to complete the project. It breaks down the work based on the sequence of activities or workflows involved in delivering the product or service.

Structure - Organizes the project into processes, procedures, or phases, detailing the steps or activities required to move through the project lifecycle.

Advantages - It provides insight into the steps and processes involved in delivering the project, helping with resource allocation and scheduling. It works well when the project requires specific workflows or well-defined phases to be followed in sequence.

Dictionary

When analyzing each work package in a Work Breakdown Structure, it is essential to capture detailed information to ensure proper management, execution, and tracking of the project. A WBS Dictionary is typically used to document this information, providing an organized description for each work package, task, or deliverable. This ensures clarity and consistency across the project.

Key components:

WBS Work Package

Task: Specific task/activity

Estimated Level of Effort: By first order estimation and refine through iterations (in hours)

Owner: Specify primary owner and secondary owner

Resources Needed: Number and specialty of engineers, manager, subcontractors, Design, build, test facilities, hardware/software tools, budget

Work Products: Quantified output of work, Cyberphysical product, Documents, Deliverables, Recipient of delvierables

Description: Precise description of task and breakdown of what each subtasks are involved

Input: Define connection to other work packages

Dependencies

Risks: First pass on identifying risks, The lower the level of the work package, the more technical risks dominate, Risks related to scope of tasks, resources, budget, effort allocation

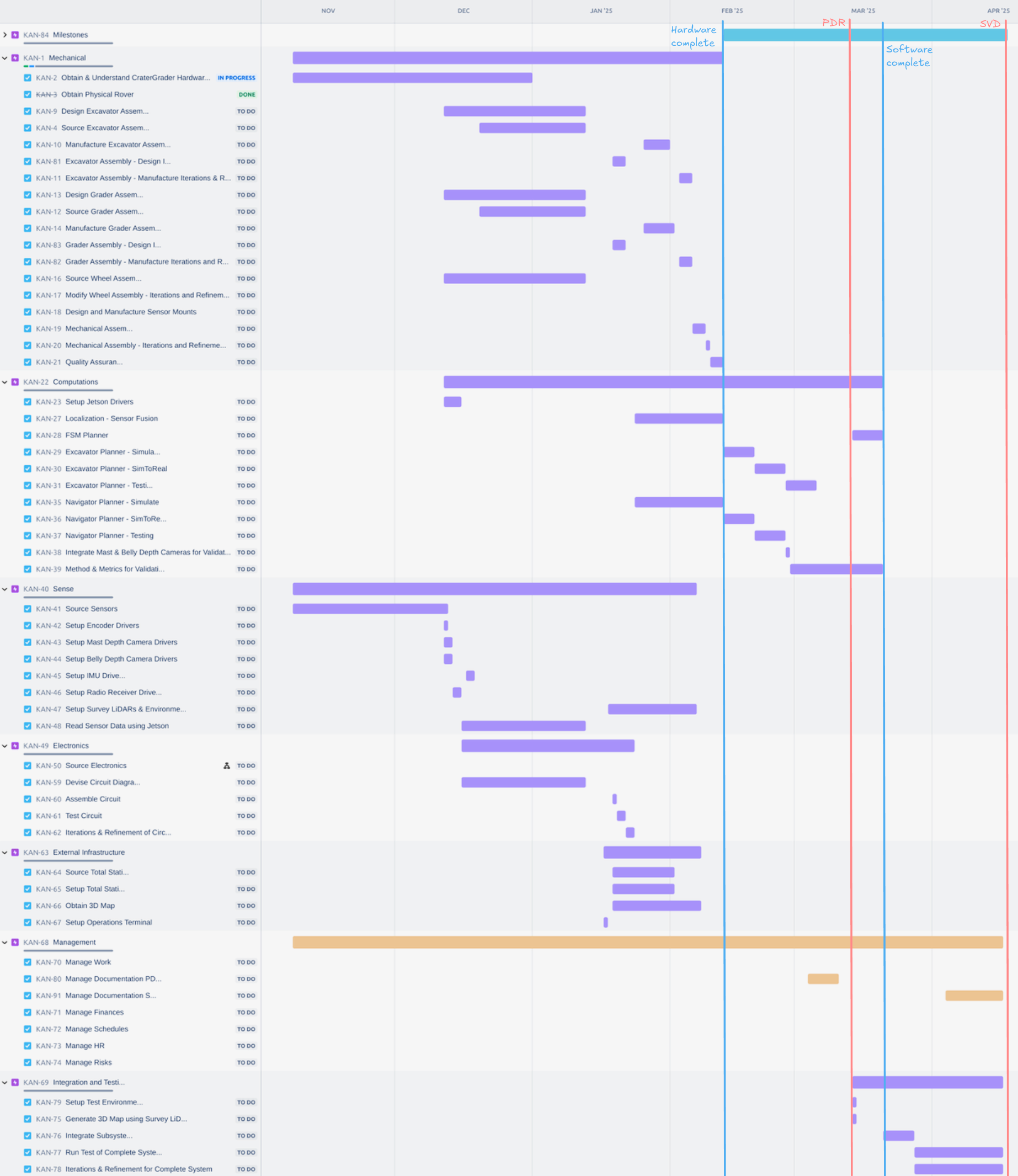

Develop a Schedule

The following factors need to be considered for effective estimation of a project schedule:

Work Effort vs. Duration: Work effort refers to labor hours (e.g., 40 hours); duration accounts for calendar time, factoring in availability and efficiency.

Account for non-project activities such as administrative tasks, approvals, and external dependencies such as delays from vendors.

Estimation at the Lowest Level: Break tasks into smaller work packages or activities to ensure precision, and roll up estimates for an overall view.

Skill Set and Expertise: Identify and assign specific skills needed for the task; Leverage experienced resources for faster, more accurate task completion; Use lessons learned from similar projects to improve accuracy.

Prior Estimations and Performance: Analyze past estimates to refine current ones; Identify recurring inaccuracies to enhance future planning.

Contingency Planning: Add time and cost buffers to account for risks and unforeseen challenges; Link contingency to specific risks identified in the WBS.

By addressing these considerations, estimates become more realistic, reducing risks and improving project outcomes.

Milestones

Types of milestones:

External: These are mandated by the sponsor

Required Internal: Based on project flow such as integration, first roll-out, etc.

Non-mandatory Internal: Used to facilitate management of activities/tasks, costs, schedule, and risks

Comments on milestones:

Milestones are significant zero-duration events in the life-cycle of a project

Changing a milestone impacts all facets of the project

If an external milestone is changed, a partial or full project re-planning is required

External milestones are rigidly defined and cannot be changed unless there is formal contract modification

Internal milestones should be treated as if they were external

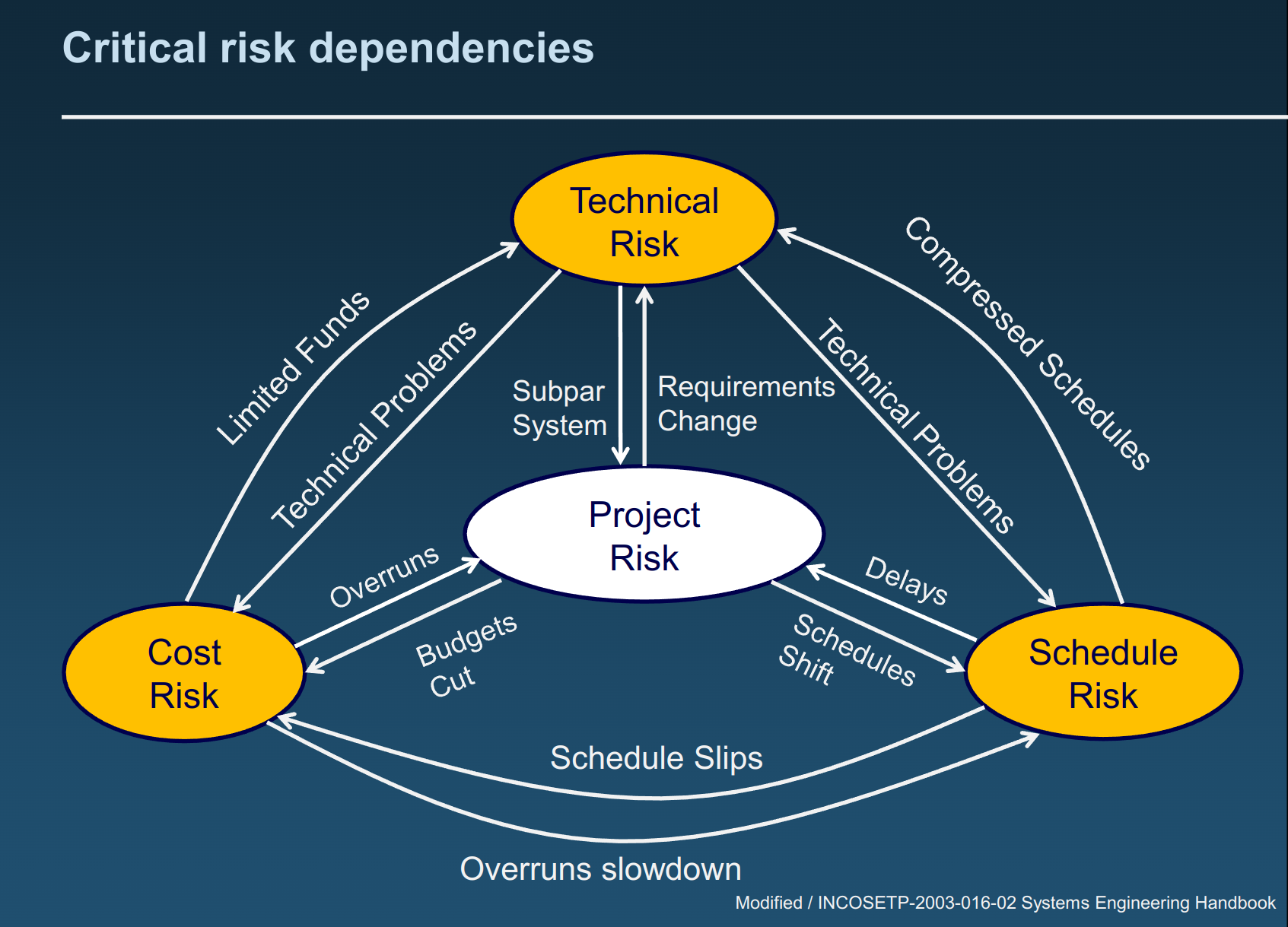

Risk Management

Issue vs Risk

Issue: An issue is a current problem or challenge that is actively impacting the project. It requires immediate attention to resolve or mitigate its impact.

Risk: A risk is a potential problem or uncertainty that could occur in the future and might affect the project. It requires planning to prevent or minimize impact if the risk materializes.

Components of a Risk

Root cause: The underlying reason or source of the risk. Identifying the root cause helps in understanding why the risk might occur and provides insights for mitigation strategies

Probability: The likelihood or chance of the risk occurring. This is often assessed on a scale (e.g., low, medium, high) or as a percentage. Understanding probability helps prioritize risks and focus on those more likely to happen

The potential impact or effect the risk would have if it materializes. Consequences can affect scope, schedule, cost, or quality and are often quantified in terms of severity (e.g., minimal, moderate, critical)

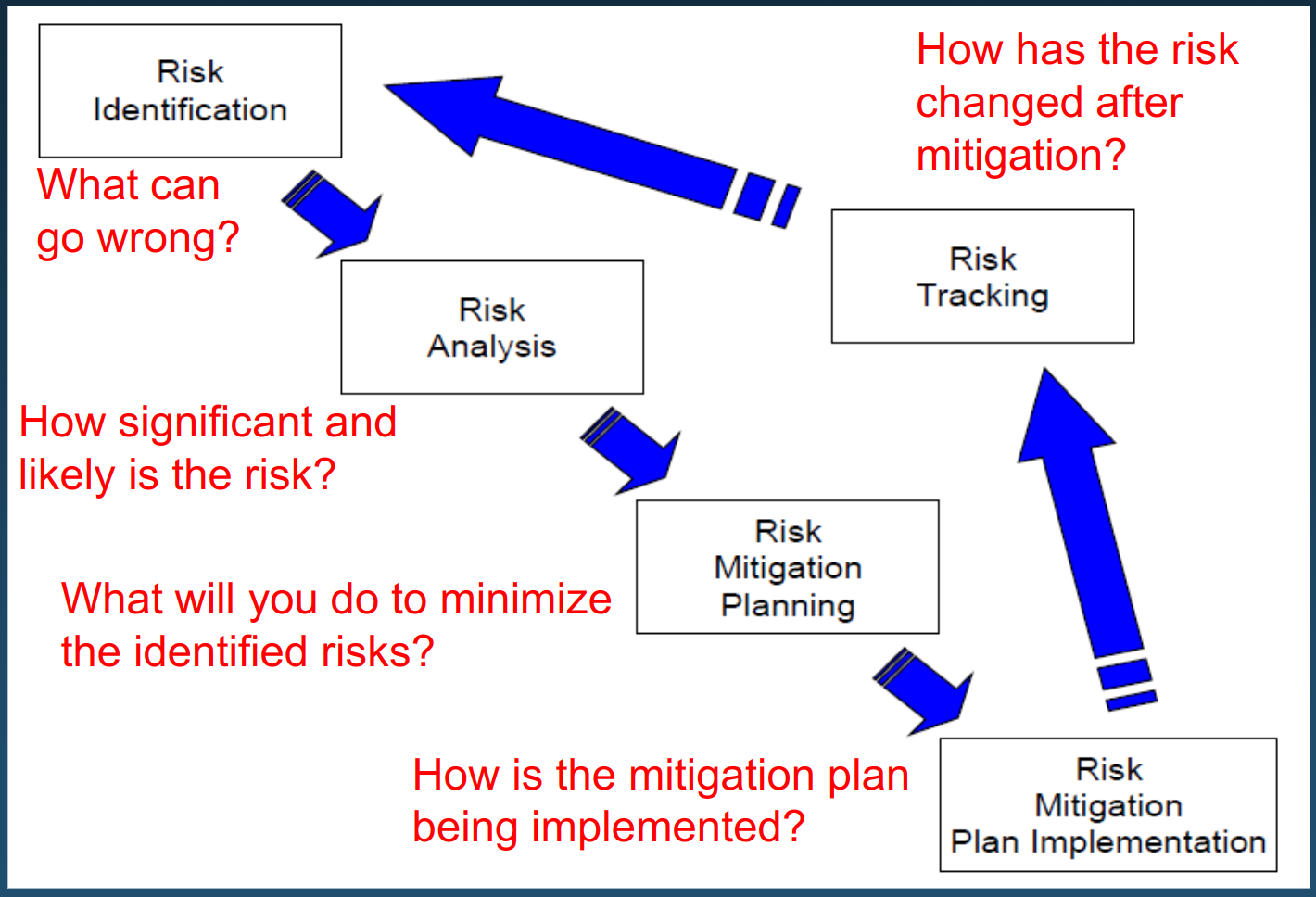

Approach

The following approach should be followed to manage risks in a project:

Identify risks (what could go wrong?):

Review your WBS work packages

Examine what could go wrong

Compile a list of potential risk root causes

Analyze risks (how big is the risk?):

Use likelihood and consequences matrix to rank

Be conservative for the initial pass

Discuss with stakeholders

Formulate action plan:

Identify simple, realistic actions you will take - eliminate root cause if possible, or transfer risk if possible, or assume risk and continue

State what will be done, when, and by whom

Set success metrics to mitigate risk (specific quantitative targets)